As Russia prepared to attack, we were told that the country feels it is surrounded and is insecure. But we have been told this many times over the years and we should be very careful with such claims. Russia has considered itself to be insecure ever since it emerged from Tartar rule as the Grand Duchy of Muscovy in the 15th Century. That emotion is what motivated it to conquer other territories and grow year by year and century by century, to become one of the biggest empires the world has ever seen – which it still is.

The Ukraine on the other hand – with few natural frontiers and historically a neighbour of powerful states such as Russia, Poland, Germany and the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires – has never had an enduring state of its own, while its 30 recent years of independence have been very uncertain all the way through.

So which of these two countries is the insecure one? Huge, powerful Russia with a long imperial tradition that has developed over a period of nearly 900 years since Moscow’s foundation? Or the Ukraine – in area, the largest wholly European country of all but always subordinate to whichever neighbour happens to be the strongest?

Now, a third of a century after the Ukraine finally gained independence, Russia’s ruler has declared that the nation does not even exist and its state is illegitimate. This follows constant browbeating and interference since 1991, via television channels beamed across the border, financial pressure, cyber attacks and the manipulation of parts of the Ukrainian state itself. (It may be President Zelensky’s attempt to purge his country of media disinformation from Russia that led to the present crisis.) I witnessed some of this myself as early as 1994, when I monitored media coverage of national elections in Donetsk (mainly) and Kharkiv in the east of the country. Those elections were very corrupt and at least partly fraudulent, with some evident coordination with Moscow. Part of my report’s conclusion is quoted below.

For the first two decades after independence, Ukrainian politics was deadlocked in a debate whether the country should face west towards Europe and assert its Ukrainian identity, or east towards Russia, acknowledging cultural connections with that country. The deadlock ended suddenly in 2014 with Russia’s annexation of the Crimea and fomenting of armed revolt in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Russian officials had insisted the Ukraine was their closest friend, but friends do not behave like that. Ukrainians became hostile to Russia overnight.

Russia’s numerous attacks since 1917

These acts of aggression were far from the first since November 1917, when in the Constituent Assembly elections Ukrainians voted in a large majority for pro-independence parties, giving the Bolsheviks only 10 per cent support. Since then, rulers in Petrograd and Moscow have taken the following actions against the Ukraine:

- 1918-19: Bolsheviks attack and conquer, making the Ukraine part of the USSR in 1922 but managing to make Kyiv the capital only in 1934;

- 1932-33: a savage famine (‘Holodomor’) among peasants, especially in the Ukraine, politically directed by Stalin (the Bolsheviks having little support among either peasants or Ukrainians);

- 1939: invasion of the Western Ukraine (which was ruled by Poland) under the Hitler-Stalin Pact;

- 1945: renewed invasion and reconquest as the Soviet Army drove the Germans out, provoking guerrilla resistance until the early 1950s;

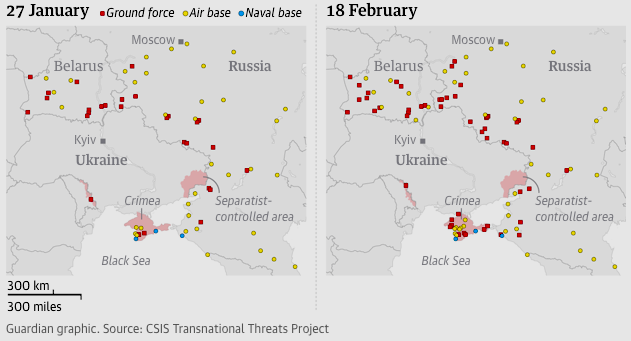

- 2014: renewed attacks by Russia, in a war that still continues;

- 2022: recognition as ‘independent’ of the Donetsk and Luhansk ‘republics,’ whose initial rebellion had been Russia’s doing.

Modern Ukrainians point especially to the Holodomor, which was forlong described as an ideological drive to collectivise Soviet agriculture. It was a particularly savage version of what would now be called hybrid warfare: aggressive attacks which take other forms than direct assault. Since 1990 they have occurred frequently in Russia’s neighbours, with Donbass-like ‘frozen conflicts’ also in Georgia and Moldova, and cyberattacks in the Ukraine, Estonia and elsewhere.

Russia and Ukraine – separate histories

The name ‘Ukraine,’ which means ‘Borderland,’ still sums up the attitude of many Russians towards that country, whose history differs from Russia’s in that it escaped the mediaeval Tartar ‘yoke’ to remain under European influence. To Russians of that sort, the Ukrainians are not in fact a separate people and their language is not even authentic. They also maintain that Kyiv was the birthplace of the Russian state and nation. Vladimir Putin places himself squarely in that camp, as was clear in his television remarks on February 21st, 2022.

However, the city-state of Moscow and Grand Duchy of Muscovy were in reality the local agents of the despotic Tartar rulers. By 1480 Muscovy had conquered all the other city states of Russia, and Tartar rule was over. The revolutionary Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev, educated in Kyiv, later described the Grand Duchy at this time as ‘a Christianised Tartar kingdom.’ Unable to defeat the Poles, Lithuanians and Swedes in the west, Muscovy then rapidly expanded eastwards into Siberia. To the south it faced repeated raids from Turks across the open country that is now called Ukraine. In order to counter this, Muscovy placed popular subservience to its military needs above all other requirements and expanded gradually southwards, after each conquest creating a new buffer zone which in turn was later absorbed and integrated into Russia. But Russia’s old nightmare recurred with invasions by Napoleon in 1812 and Hitler in 1941.

Meanwhile, in 1654 a young Ukrainian Cossack state under its chosen Hetman or leader, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, signed the Treaty of Pereyaslav with Russia for protection from Sweden’s expansionism. This turned into a process of gradual absorption under full Russian rule, completed before the end of the 18th Century. Most Ukrainians were peasants (many of the landowners still Polish) and their culture was heavily repressed under the Tsars’ rule.

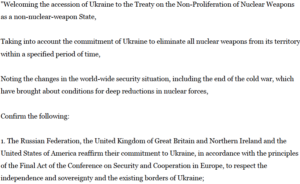

So beware pleas from Russia about its insecurity. The US and UK made this mistake in listening to similar pleas from President Yeltsin in the 1990s. This made them help him to disarm the Ukraine, removing its nuclear arms and handing to Russia the naval port and fleet of Sevastopol – which is now being mobilised against the Ukraine. To get Kyiv to accept this, in 1994 all four countries signed memorandums in Budapest to ‘confirm’ the Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. But this meant nothing, as we saw when Russia brazenly violated the deal in 2014, to a tepid response from the two Western signatories. Without that disarmament deal in place, Putin would never have stolen the Crimea or destabilised the Donbass 20 years later.

Likewise, since the USSR broke up there has been a lot of Doublespeak about NATO membership. The rhetoric is that the Ukraine, Georgia and other ex-Soviet countries are free to apply to NATO. But everyone knows that their applications would be rejected or ignored. So those countries which most need foreign protection – from a powerful, revanchist neighbour – cannot get it. This tacitly connives in Russia’s imperious demand for a ‘sphere of influence,’ and gave Putin the confidence to invade.